One of the best autobiographies ever written happens to be one of the first, one of the darkest, and one of the most creative. The title of Thomas de Quincy’s 1821 classic says it all: Confessions of an English Opium Eater. Yes, it’s about addiction, but he uses the subject to explore something ground-breaking for the time – the inner universe.

We now live in an age of self-obsession. The era of everybody’s autobiography, as Gertrude Stein said. We all have our story, celebrities and politicians sell memoirs, we’re surrounded by reality TV and podcasts about personal growth, we live in a culture of self-development, the age of me.

De Quincy’s story begins with his pains and afflictions – toothache, poverty, hunger, sufferings – that ‘threatened to besiege the citadel of life and hope’, in his words. Crucially, he says that usually ‘Guilt and misery shrink, by a natural instinct, from public notice: they court privacy and solitude’.

His book is a confession because he says that usually people omit the ugly parts of their character and emphasise their success. He wanted to challenge that.

Then, he describes the relief of taking opium for the first time – ‘what an upheaving, from its lowest depths, of the inner spirit! what an apocalypse of the world within me!’

He describes an ‘abyss of divine enjoyment’ and ‘ a panacea for all human woes: here was the secret of happiness, about which philosophers had disputed for so many ages, at once discovered: happiness might now be bought for a penny, and carried in the waistcoat pocket: portable ecstasies might be had corked up in a pint bottle: and peace of mind could be sent down in gallons by the mail coach’.

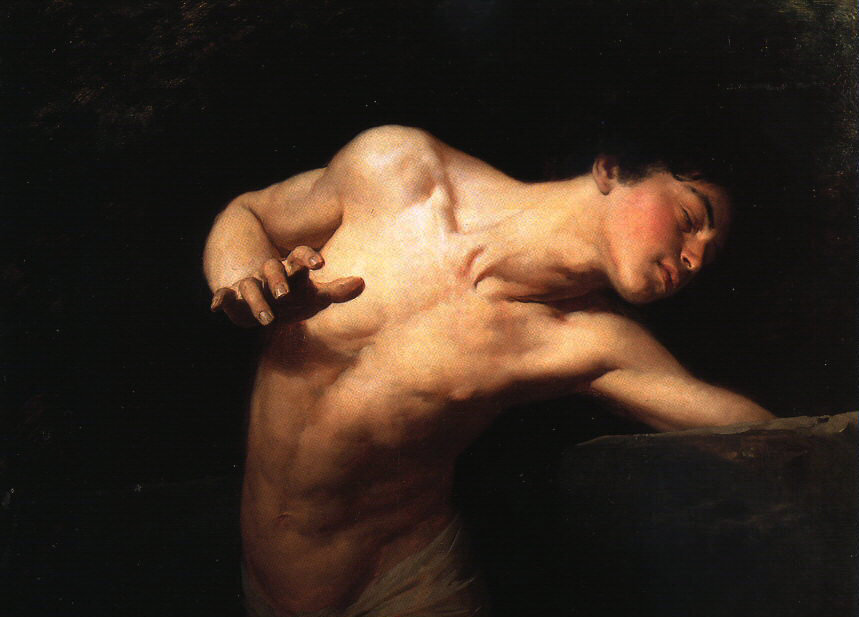

He uses the experience of his opium addiction to explore, psychologically and innovatively, that ‘abyss within’ – that ‘apocalypse of the world within me’.

This gazing into the abyss within is a mode of self-exploration that is still unfolding culturally. Compare the popular TV shows of this year with those of just twenty years ago. From the Last of Us to the Bear to Succession – these new shows are not what they’re ostensibly about on the surface – zombies, cooking, or business – but are about something much more universal – character. Much of their genius – much like Oppenheimer, for example – relies on these shallow depth of field close ups on the intense emotions displayed on the torn character’s face.

So where did this inward gaze come from? Before de Quincy’s time, we have to remember that knowledge, traditionally, was not about what’s in here – endogenous – but what’s out there –exogenous. Everything from moral rules coming from god, to science coming from studying the world, to art coming from ancient models and classical forms – was about studying and learning from the external world.

There’s a great book on the early Ancient Greeks of Homer’s time that influentially makes the case that the people of that period saw their emotions, passions, angers, and desires not as coming from within but as being placed in them by the gods.

Agamemnon says that Zeus put wild ate – the goddess of mischief and delusion – in him, and made him act in a way contrary to how he usually would – he says the ‘plan of zeus’ was fulfilled.

Other characters talk as if gods had taken away, changed, or destroyed a normal way of thinking and replaced it with another.

In other words, character came not from within but from without. Remember, the Ancients had no concept of personality, of biochemistry, they genuinely believed in their gods. Think about how powerful our imaginations are – why wouldn’t you believe that an intense of experience of anger, say, and a loss of self-control was something planted there by the gods.

To take one more example, in the Christian framework, the self is always in reference to god. St Augustine may have written the first autobiography – The Confessions – in the 4th century, but his aim was to conform his behaviour to the external rules of Christian teaching and god’s will, not to discover some true self within.

The Medieval period was defined by roles you were born into – craftsman, butcher, peasant, lord – the rules were laid down, you didn’t question them. But in de Quincy’s time all of this was changing.

De Quincy was obsessed with two poets: William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge – he idolised them, wrote letters to them, befriended them, and travelled here to the English Lake District where they lived. He idolised them because, like other writers of the time like Goethe and philosophers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau – they were all working out a new idea of the self.

Wordsworth, before de Quincy, also wrote one of the first autobiographies – a very long poem called the Prelude about ‘the growth of a poet’s mind’ – all about his childhood experiences. He admitted that, ‘it is a thing unprecedented in literary history that a man should talk so much about himself’.

Wordsworth believed, adopted philosophical ideas in Germany from people like Kant, that our inner life – the framework, structure, ideas, emotions, of the mind and body – shapes the information we get through the senses and patterns it, colours it, transforms and raises it – so that everyone sees a lake, for example, in a different way, with different memories, different goals and ideas. This was radically new.

It all started with Rousseau, who, not long before in the 18th century had a profound realisation. If, as he believed, it was the world, political systems, and social norms around him – those exogenous features – that were oppressing ordinary people, keeping them in chains, where was truth to be found? It could only be found, he decided, within.

Rousseau opened his autobiography – again, one of the first, probably the first, and again titled The Confessions – with this influential passage: ‘I am made unlike any one I have ever met; I will even venture to say that I am like no one in the whole world. I may be no better, but at least I am different’. Because of this he said, ‘I should like in some way to make my soul transparent to the reader’s eye’.

The historian W.J.T. Mitchell even described Rousseau as the first modern man – ‘the great originator’.

Goethe, inspired by Rousseau, said that he turned into himself and found a world. Rousseau said his project was one that had ‘no model’, and would have ‘no imitator’.

It was an act of pure, singular, individual, irrepressible creativity – from within.

This spirit of the age had a profound affect on many writers. Wordsworth wrote so much about this place because it was where he was from. He described the psychological ‘spots of time’ that influenced his individual character.

Personal and local stories from places like this one: Dungeon Ghyll Force – as a place where lambs almost drown because the shepherd’s boys aren’t concentrating – he describes their inner worlds – their ‘pulses stop’, their ‘breath is lost’.

Or when he remembers stealing a boat at night when he was a child, becoming terrified in the middle of a lake at the dark imposing shapes of the mountains around him that haunted him and ‘moved slowly through my mind / By day, and were the trouble of my dreams’.

De Quincy admired all of this so much that he moved into Wordsworth’s cottage after him and when writing his own autobiography, wrote with his tongue in his cheek that there were ‘no precedents that he was aware of’ for this sort of writing.

But this is what makes De Quincy’s Confessions so innovative. He focuses on what is usually swept away in our own self-aggrandising narratives about ourselves. He says, ‘Nothing, indeed, is more revolting to English feelings, than the spectacle of a human being obtruding on our notice his moral ulcers or scars, and tearing away that “decent drapery”’.

He took Wordsworth’s exploration of emotion, feeling, the self and the natural world and applied it to his own warped experiences with opium and urban life.

He describes how opium furnished ‘tremendous scenery’ in the dreams of the eater. He writes poetically about the ‘endless self-multiplication’ of the self going up and down symbolic staircases, and talks about the ‘wonderous depth’ within.

He uses metaphors like translucent lakes and shining mirrors and waters and oceans changing, surging, wrathful, to describe the changes in our own inner lives. ‘My agitation was infinite,’ he said ‘my mind tossed – and surged with the ocean.’

Of course, this new inner self didn’t appear from nowhere. It mirrored the scientific developments of the period. When astronomers like Galileo made observations about the universe that contradicted that taught wisdom of the Bible, all of these poets and philosophers were saying: ‘what about the universe within?’

Wordsworth’s spots of autobiographical time, de Quincy’s artistic description of personal challenges and addiction, Lord Byron’s model of heroic outcasts on voyages of self-discovery – all provide the groundwork for modern psychology, the modern self, and for the core injection of the modern world: create yourself as something new.

The autobiographical self is the model that helps us traverse the world. As psychologist Qi Wang says, the autobiographical self is, ‘self-knowledge that builds upon our memories and orients us toward the future, allowing our existence to transcend the here-and-now moment’.

This had an incalculable effect on the culture and politics of the modern period. These writers were a sensation across Europe and anyone who argued for individual rights, freedoms, the power of ordinary people, drew on them in some way.

On the other hand, I’s produced the narcissism and obsessions with the self we see everywhere today. We no longer look outward as much, but spend a lot of time naval-gazing in.

I think the challenge of this century will be whether the world within can be reconciled with the world without.